Around 2015, Kazakhstan saw the rise of Q-pop, led by the boy band Ninety One. A decade on, the cultural tension remains: while youth artists enjoy greater visibility, many observers argue that freedom of expression is still shaped by a silent boundary — ‘you can make music, but not stir too much controversy.

A little over a decade ago, five young men in earrings and pastel clothes released “Aıyptama!” (“Don’t blame me”) – a slick, catchy track in Kazakh, with a video that looked like it came straight out of Seoul. The group, Ninety One, was born out of a reality TV show modeled on the K-pop system.

At the time, Kazakh-language pop had little presence on mainstream radio or TV, where Russian-language and Western hits dominated. Much of the Kazakh-language music most people heard came from weddings and folk performances rather than commercial pop charts. Occidental pop, rock and Russian-language hip hop ruled the charts. So, when Azamat Zenkaev (AZ), Dulat Mukhamedkaliev (Zaq), Daniyar Kulumshin (Bala), Batyrkhan Malikov (Alem), and Azamat Ashmakyn (Ace) debuted as a group, they looked and sounded like nothing the local music scene had ever seen.

Their appearance sparked outrage. In Karaganda, a 2016 concert was canceled after protests. “We are against them because they dye their hair and wear earrings!” a demonstrator shouted, captured in the 2021 documentary Men Sen Emes (Sing Your Own Songs) by Katerina Suvorova. “No parent would want their son to look like a woman,” a conservative activist added. Even their producer, Yerbolat Bedelkhan, noted, “They shook up Kazakh show business with their unusual looks.”

And yet, their rise was unstoppable. Despite boycotts and online abuse, Ninety One topped national charts. Each video release became an event. Over time, their success helped make gender-fluid aesthetics more visible in Kazakhstan’s pop scene — and made singing in Kazakh fashionable again among young audiences.

But their aesthetics stood in sharp contrast to the state-promoted model of Kazakh masculinity.

Ninety One; image: JUZ Entertainment

Revival and Restriction: The State’s Masculine Ideal

In 2017, then-President Nursultan Nazarbayev launched Rukhani Zhangyru – a sweeping state program for “spiritual renewal.” Its goal was to forge a unified Kazakh national identity after decades of Soviet domination, largely by reigniting traditional values. Streets were renamed after historical khans, a National Dombra Day was established, and the country began shifting from Cyrillic to the Latin alphabet.

But the cultural revival came with a gender script. School textbooks were rewritten, according to a 2021 Rutgers University study, to cast masculinity as a blend of strength, rationality, and emotional restraint. The ideal Kazakh man – the Batyr – was reimagined as a stoic warrior of the steppes.

In this context, Ninety One’s aesthetics didn’t fit in. “Many thought Q-pop artists didn’t act like ‘real Kazakhs’,” Merey Otan, a musician and PhD candidate at Nazarbayev University told The Times of Central Asia. “Wearing makeup, earrings, or bright clothes, expressing emotions or sexuality – these all clashed with a rigid model of masculinity.”

Some other pop groups, however, had already challenged this model.

According to Nargiz Shukenova, director of the Batyrkhan Shukenov Foundation and producer of the encyclopedic, 91–23: The popular music of independent Kazakhstan, the Kazakh pop scene had been experimenting for decades. “To say pop started with Ninety One is inaccurate. Even during the Soviet era, it drew inspiration from Western bands such as The Beatles, Depeche Mode, and Earth, Wind & Fire.”

Orda, the pop group led by the producer Bedelkhan, was an early pioneer. “Because they wore earrings and had a style deemed too feminine, they were called ‘freaks’,” Shukenova recalls.

What changed with Ninety One was timing and resonance.

A Generation Looking for Air

“The youth wanted something that connected their roots to the modern world they live in,” Shukenova told TCA, and Ninety One struck that nerve. Urban, digital-native fans wanted to reclaim the Kazakh language and rediscover local folklore – without denying the parts of their identity shaped by the internet and globalization.

The band gave them all that. Fans named themselves “Eaglez”, after the Kazakh national emblem. They even coined the term “Q-pop” (short for Qazaqstan pop) in the Latin alphabet. Rapidly, each one of their clips went viral.

Their popularity grew so strong that even former haters came around. “Ex-anti-fans started listening,” notes Otan. “The fact that they sang almost exclusively in Kazakh helped promote the language and tied music to the national identity.”

For N.B., a member of Q-pop group ALPHA formed in 2019, Ninety One was a revelation. “My first impression was freedom,” he told TCA. “Q-pop isn’t traditional and that’s what I liked. In 2015, teens needed air. Q-pop gave us that.”

ALPHA; image: recentmusic.com

From Love Songs to Protest Anthems

At first, Ninety One mostly sang about love, self-confidence, and resilience. But in 2019, their tone shifted. The single, “Bari Biled,” tackled corruption, environmental degradation, and social injustice, striking a chord with young listeners disillusioned by broken systems. A year later came “Taboo,” a collaboration with rap collective Irina Kairatovna, whose sharp social commentary and gritty blend of Russian and Kazakh pushed underground energy into the mainstream.

“Young people love songs that address real issues,” observes Otan. And it’s not just in pop or rap. After the COVID-19 pandemic, new scenes flourished online.

“For artists, it used to be either patriotic or commercial music,” says Shukenova. “Social media created a third way.”

One example is Qazaq Indie, a label born on the platform VK in 2017. Its first breakout star was Samrattama, a long-haired singer-poet embodying the identity struggle shaping Kazakhstan’s music scene. His latest project, Barsakelmes – a collective hybrid performance mixing traditional and electronic music with the group Steppe Sons – quietly ventures into delicate territory. By exploring decolonization through Kazakh legends and the Aral Sea tragedy, he touches on a subject few artists have dared to explore. “I’m ‘decolonial’ in the sense that I’m changing my own paradigms, my ways of seeing,” he says.

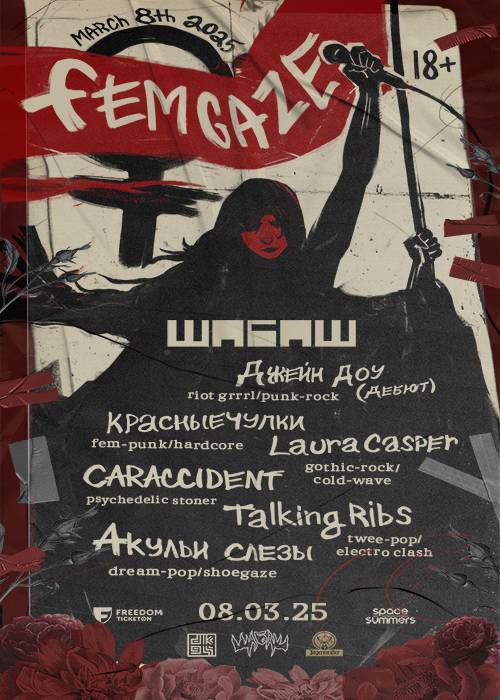

Social criticism has become even more direct in tracks like “Obal oilar-ai” (“These Guilty Thoughts”), a collaboration among indie musicians such as Dudeontheguitar and Jeltoksan, addressing poverty, corruption, and everyday despair. Even punk has joined the wave. “We’re seeing all-female fem-punk bands like Krasniye Chulki (Red Stockings),” notes Otan. “Their raw energy challenges gender norms in a rock scene long dominated by men.”

FEMGAZE 2025 featuring Krasniye Chulki; image: @kair_fltt

Free to Sing, but Not Everything

But artistic freedom remains limited; criticism may be less virulent than in 2015, but it persists. “It’s less violent now, yet mindsets don’t change overnight,” say A.Boo, I and N.B. from ALPHA. Otan agrees: “If someone like Samrattama reached Ninety One’s level of fame, there would still be resistance, though weaker than ten years ago.”

As for freedom of expression, censorship is often indirect. “There’s no official censorship, but a lot of self-censorship,” Otan notes. She recalls seeing a band at the OYU Festival – an annual celebration of Kazakh art held since 2022 – perform a political song without lyrics, only as an instrumental. “It says a lot about the fear of speaking out,” she adds.

ALPHA deliberately stays away from politics. “It’s not our role,” they say.

The subject remains fraught. In December 2024, rapper Karim Asylbekov was charged with “hooliganism” after performing a song about social injustice. That same year, a comedian was briefly detained for “obscenity” after joking about President Tokayev’s “Zhana Kazakhstan” slogan.

Kazakhstan may have moved past the open outrage of 2015, but a quiet message still lingers in the cultural airwaves: Kazakhstani artists can make music – as long as they don’t make too much noise.